Some time about 1995 I noticed that I was writing a lot more concurrent code than the other programmers. It was almost as if someone was deliberately pushing it in my direction… That theme never really changed.

Some time about 1995 I noticed that I was writing a lot more concurrent code than the other programmers. It was almost as if someone was deliberately pushing it in my direction… That theme never really changed.

I was rather surprised then when a developer made a comment on something I’d written a few years back, because I was pretty confident I’d covered all the bases.

public class SomeServer

{

private readonly Dictionary<KeyType, ValueType> queries = new Dictionary<KeyType, ValueType>();

//stuff

public void PerformLookup(string someQueryTerm)

{

//some logic...

lock(queries)

{

//some more logic

}

}

}

The comment was:

Please use a separate lock object. e.g. private readonly object _queriesLock = new Object();

Eh? What?

OK, hands up I missed this. I learnt to use basic concurrency tools way before C# existed. For me C#’s ‘lock’ construct was great because it allowed me a very clear and concise way to use a monitor. As far as I was concerned there was no downside. Why on earth would I want to use a separate lock object?

There are 2 things you need to be really careful about when using a lock in this way.

You must carefully manage the lifetime of the locked object.

Imagine above if ‘queries’ were not a readonly object created at instance initialisation. Imagine if someone did…

lock(queries)

{

//stuff

queries = new Dictionary<KeyType, ValueType>();

}

You have to make sure that the locked object is instantiated before the fist lock is taken out and you must make sure that it is not reassigned in any way until after the last lock has been exited.

If you don’t it leads to all different flavours of bad.

If you instantiate a separate lock object at object initialisation, an object that has no purpose other than as a lock, then you know it’s there at the start and the chances of someone messing with it before the end of the last lock are very significantly reduced.

You must be careful not to expose the locked object externally

C# allows an implicit monitor to be created on any object. You can use that monitor by wrapping the object in a ‘lock’ statement.

If you wrote the class to use, say a mutex explicitly rather than the implicit monitor there’s no way you consider making the mutex externally accessible…

public class SomeServer

{

private readonly Dictionary<KeyType, ValueType> queries = new Dictionary<KeyType, ValueType>();

public Mutex _queryLock = new Mutex();

//stuff

public void PerformLookup(string someQueryTerm)

{

//some logic...

_queryLock.WaitOne();

try

{

//some more logic

}

finally

{

_queryLock.ReleaseMutex();

}

}

}

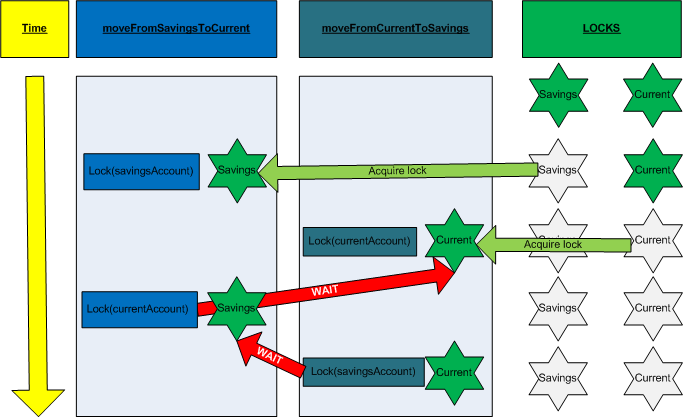

That’s complete madness – any other class can mess directly with the lock and cause all sorts of unwanted behaviour. Deadlocks are a particular hazard here and compound deadlocks can be really tough to debug.

If you’re using the implicit monitor via the ‘lock’ construct however and you expose the locked object beyond the scope of the class, you are effectively also sharing the monitor.

public class SomeServer

{

public Dictionary<KeyType, ValueType> queries {get; private set;} = new Dictionary<KeyType, ValueType>();

//stuff

public void PerformLookup(string someQueryTerm)

{

//some logic...

lock(queries)

{

//some more logic

}

}

}

public class SomeOtherClass

{

private SomeServer myServer=new SomeServer();

public void SomeMethod()

{

lock(myServer.Queries)

{

//some logic

}

//or worse...

Monitor.Enter(myServer.Queries)

//and the Monitor.Exit is in another method that might not get called

}

}

If you use a separate lock object that you know is private and will always be private then you don’t have to worry about this.

Having written this pattern many, many times in many different languages I’m not likely to fall into either trap. That’s not all that being a good developer is about though.

Now, this might seem like a strange tangent but bear with me. I learnt to use an industrial [machine] lathe when I was a kid. They teacher drummed 2 things into us.

- Do not wear any loose clothing (e.g. a tie)

- Do not leave the chuck key in when starting the lathe

The reason these 2 things in particular were so important was because the lathe I learnt to use had no guard. Either of those 2 mistakes could be fatal.

I’m glad I learnt that, but given the choice would I use the lathe with a guard or the one without? It’s a no-brainer.

We have the same situation here. Unless we’re writing something very specific where memory is absolutely critical, there’s no harm in creating an extra lock object. It provides a useful safeguard against a couple of gotchas that could cause real headaches in production.

Software development purists will be wringing their hands, but they’re not what commercial software development is about. It’s about writing code that does the job in a simple, safe and maintainable way. That’s why using a separate lock object is C# best practice and that’s why I fully support it.