Reading Time: 5 minutes

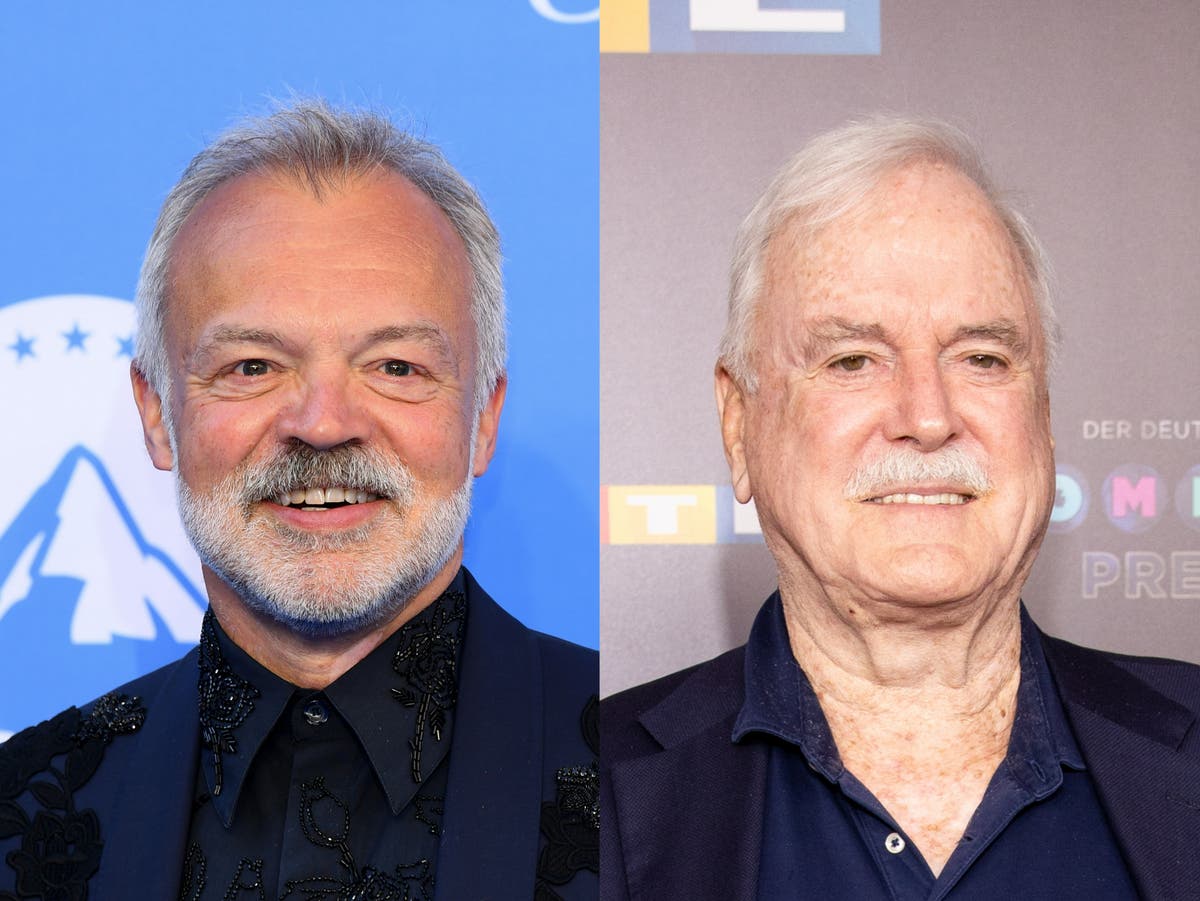

John Cleese is a well read, intelligent and usually eloquent man. He’s made some pertinent observations in the past, ones about which nobody can doubt his good intentions. However, I could say exactly the same about Enoch Powell.

Lately Cleese has swallowed the concept of Cancel Culture and is banging on about it like some old white men have become prone to in the past few years. Actually, I get his point, but the problem is – for the most part – his, not ours. Graham Norton hits the nail on the head, Cleese is finding himself accountable for his words for the first time and he’s not dealing with that all too well.

Graham Norton responds to John Cleese’s complaints of ‘Cancel Culture’

Talk show host reportedly described Cleese as ‘a man of a certain age who’s been able to say whatever he likes for years’

Going after someone’s platform because you don’t like what they’re saying is nothing new. The soap box had barely been invented before it was kicked out from beneath a speaker because someone didn’t like what they were saying. It might be underhanded and cowardly, it might be a better world if nobody did it, but it’s commonplace and always has been.

What’s changed, then? Freedom from the consequence of your words is a privilege, but whereas in the past someone in a position such as Cleese would be above the threshold for that, they now find themselves below it. That’s it, pure and simple.

“But”, I hear you ask, “if it’s a matter of privilege, shouldn’t we be trying to extend that out to everyone?”

In an ideal world freedom of speech would be an absolute. But even in that ideal world, all freedom of speech means is freedom from sanction or oppression by the state (or state actors). In theory everything is (or could be) controlled by the government, so it’s paramount to the functioning of a democracy that you must be able to criticise the government without fear of sanction from the government or its agents. That’s the fundamental reason we have a right to freedom of speech.

There are two key points here:

- You may speak, but nothing about free speech says anyone has to listen or give you a platform.

- Your only indemnity is against sanction from the government and its agents. The right to free speech doesn’t protect you against any other consequences.

Yes, of course we can argue about the extent of the agents of the government, but if your local pub throws you out for trying to hold Combat 18 meetings there, that isn’t a freedom of speech issue.

Enter The Internet

Let me put a hypothesis to you. The Internet has changed our lives enormously. It’s facilitated (more) direct targeting, but it’s also added a horizontal layer across public channels that wasn’t previously there.

What do I mean? In 1968 you could go to the pub with your similarly minded friends and spout whatever nonsense you liked. You’d be very unlucky if there were any negative consequences – but that’s only because nobody who was interested heard you. Even politicians could get away with making inflammatory speeches to local party groups, because nobody outside the room was listening. Enoch Powell had to actually tell the media that he was going to “send up a rocket” in order to get himself cancelled, otherwise his ill-judged “Rivers of Blood” speech might have slipped by unnoticed.

The Internet (and technology in general) has changed that. You might subscribe to The Telegraph or The Guardian. Think of them as vertical channels, they feed you news based content on a variety of different topics, applying their own particular filters and biases.

In 1968 a lot of people kept newspapers for a few days, so that if something came up they could look back at what was being said. They were staying in vertical channels.

Ed: There was a nice visual link here to a Twitter post in which Rebecca Reid explains some of the above and another pertinent problem with British Journalism, but Space Karen has screwed up Twitter so badly that visual link previews aren’t working any more. You can still follow the old school link, however =>

https://twitter.com/mikegalsworthy/status/1584463739566583809

In 2022 if you want to find out what’s going on, you Google it, and Google doesn’t just give you your favourite news source, it gives you a selection of articles from all the major news sources. You can take a horizontal view, you can easily see what each different channel has to say about a particular topic.

This should be a great advantage, but people don’t do it because, sadly, people don’t like having their opinions challenged. Anyway, they’re not the people we’re talking about…

Expand this vertical versus horizontal concept to Twitter, Facebook, Instagram. Your normal audience on these platforms might be just your friends – the vertical – but they are public and unless you’ve locked your account, your posts can be found in searches and by algorithms covering any topic.

There are numerous groups and interested parties out there working on the horizontal, searching for, picking up on things and amplifying them. When someone with a significant platform says something they agree with, they amplify that. It gets retweeted, copied around Facebook groups, WhatsApp groups, people talk about it on YouTube and TikTok, etc. It can result in the person getting quite a boost, both in exposure but also directly through stuff like Patreon, Paypal, BuyMeACoffee etc.

Exactly the same thing happens when someone says something they disagree with. The signal gets amplified and as a result people start to go after the person’s platform, their employer, start campaigns to boycott the person’s products and businesses etc.

That’s it. That is the primary explanation for the illusion of Cancel Culture. The Internet giveth and The Internet taketh away.

Cleese; an awful lot of white suburbia, rent-a-gobs and bigots do like to stand on the battlements of their castles and yell at the peasants, certain that they are protected. But everyone’s castle is, ultimately, built on sand. Society, culture and technology change. If you don’t adapt to the changing sands, your castle will fall and you’ll end up confused, angry and lashing out at ghosts.

Nobody, it seems, is more resistant to change than old white men.

They Do Have A Point, Though…

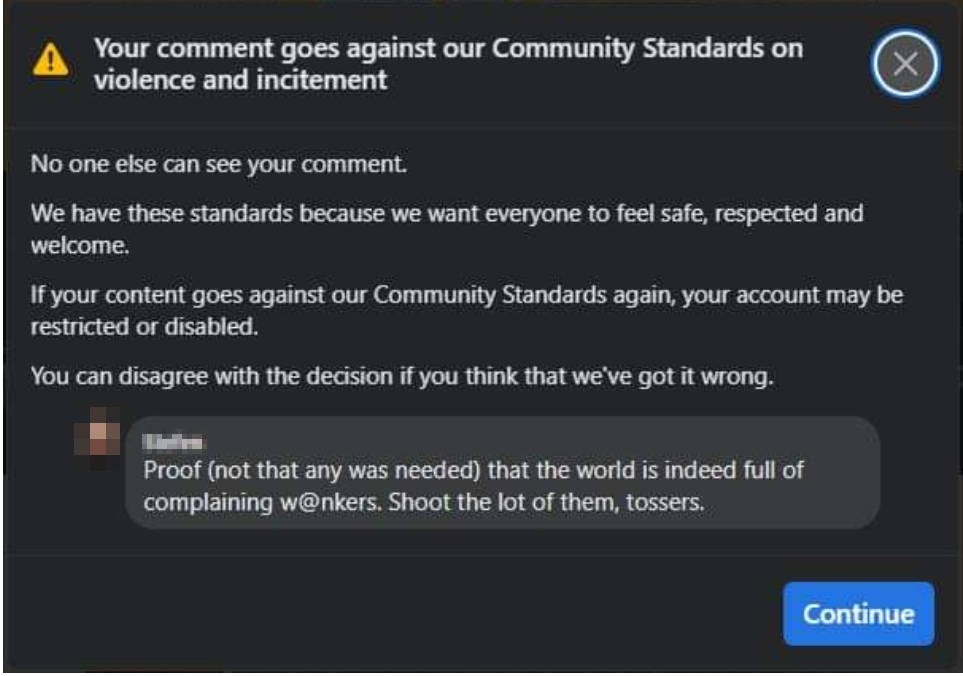

At the top I said it was mostly their problem. The fact that something is doesn’t make it right. Of course it’s right that people should be held to account for their actions, even those who haven’t in the past, but what happens is not always proportional or just.

Many years ago someone overheard me explaining The Great Replacement (a racist conspiracy theory) and mistakenly assumed I was advocating it. That person then set about what we might call today a campaign to cancel me. It took a lot of effort for me to counter that negative campaign.

Forward fast that story to today. Imagine how much further, faster that negative campaign might have got. We can see this played out on social media time and again.

Sometimes it’s a few words taken out of context and suddenly that person is the enemy.

Other times someone might give a genuinely ill informed opinion. By that I mean that their opinion was earnest, but it was based on something they’d believed but which was wrong or they didn’t realise they were lacking critical information.

They might get a few responses saying “Hey, I think you should read this…” but the storm starts immediately. The saying “bad news travels fast” is much older than The Internet, but The Internet amplifies it greatly. Conversely, “Highly Knowledgeable Person Expresses Well Reasoned Opinion” never made a headline, so the defence, the full context, the revision of an opinion never has the reach that the initial sensationalism does.

Unjustified damage is done and valid, useful arguments are lost.

It’s Mixed Bag, Then.

I’m hypothesising here, of course. I don’t know that The Internet and effortless global communication are the primary cause of these changes in our society, but at a kind of amateur sleuth level it seems rather plausible.

What we can say is that anyone who’s ever lived in a deprived area understands what accountability for their words means. As Ice-T so neatly observes, “Talk Shit, Get Shot.” Whilst we clearly want accountability to be fair, just and not involve getting “Sprayed with the ‘K”, we want it to apply equally to everyone. If all we’re seeing is accountability being extended to people who previously weren’t, that’s no bad thing.